What I have been doing

In the summer holidays I had the privilege of attending the National Computer Science School (NCSS) at the University of New South Wales (UNSW). This was a 10 day program focusing on cyber security. The general day structure was lecture, labs, lecture, labs, and then an activity. The lectures were conducted by Richard Buckland - the main cyber lecturer at UNSW. This content culminated in the “war games” at the end where all groups competed in solving challenges. Unfortunately I tested positive for COVID-19 around 3 days before the start of NCSS, so I missed 4 days of the program and content.

The content

The content covered was broken into many categories, of which I was present for two: microprocessors, and exploiting C.

The microprocessor content consisted of using simulated microprocessors created by UNSW CS students to write simple programs. The microprocessor instruction sets were very primitive, containing two registers, and no stack or block pointers. To create a function in machine code with this instruction set, each byte of memory used had to be specified, meaning more bytes overall were used by control instructions. The first challenge that I was present for involved translating a C program into machine code. I essentially became the C compiler.

One function that needed to be translated from C involved determining if a number was even or odd. Considering the microprocessor did not have a divide or multiply instruction, I had to do this in a iterative manner. By subtracting one from the number and then changing a flag between true and false until the number is 1 (the only ‘jump to x, if’ instruction checks if register one is 0), you can check if it is even or odd. Say the number is 7, and the flag starts at the false position, when you do 6 cycles of subtraction, the flag cycles an even number of times meaning the flag is false, and the number is odd (you have to consider the extra cycle to make the number 0). If it cycled an odd number of times the flag would be true, and the number would be even. It is a whole different type of thinking to python when you are so limited by instructions, a function that could be solved in a few characters in python can take hours to solve in machine code. Unfortunately I did not keep record of my exact code for this problem, and I do not have the instruction set to code it again.

There were many more similar challenges with microprocessors, with increasing instruction sets for each, my favorite of which involved stack and frame pointers. Eventually we got to calling functions by pushing the parsed variables, memory return location and previous register values on the stack, and then accessing them with the frame pointer, and popping them when they are no longer needed. This is actually how the C compiler works, so it was a good thing to learn.

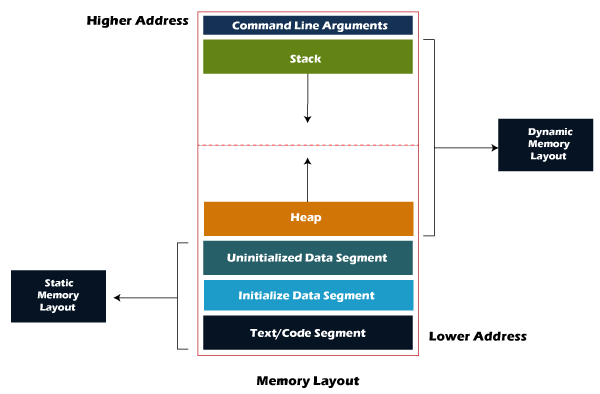

I was not present for a significant amount of the C stuff so I was not nearly as interested when it came to exploiting C. Richard Buckland however gave a great lecture on buffer overflows. Essentially because the stack is underneath (actually above growing downward) other data frames, it is possible to overflow the memory buffer into other data frames. Generally memory is formatted as stack, heap, variables, then text/code segment (the file being run), this can be seen in the below diagram.

If you push enough data onto the stack it will overflow into the heap and then into the variable data, meaning you can alter the programs data with potentially exploitable consequences. For example if you were to move the stack pointer up without adding to the stack by pushing the same data onto the stack that is stored in memory, you can keep the program intact whilst editing whatever piece of memory you want. It is also possible to do this with the heap by pushing it up past the stack, potentially even giving access to memory that isnt associated with the c program. Now-a-days buffer overflows are basically a solved issue and modern implementations of C are generally not vulnreble to overflows. The main way of doing this is by creating memory segments, and throwing a segmentation fault (at runtime) if there is no space to put the memory. This is what happens when you try to put more data in an array than was assigned.

Site tours

One of the days in the latter of NCSS was spent touring the offices of WiseTech Global, Atlassian, and Macquarie. Generally, Atlassian was a extremely modern working evironment which clearly valued the employee experience, Macquarie was highly corporate (they had butlers to give us food), and WiseTech was highly functional - a sort of mix of the two. During the tours it seemed like the companies were trying to make a positive association with their company through food. Despite us wanting to hear about the actual work at these places, they generally focused on the free food options, with WiseTech even providing us with a whole room full of pastries, cakes, and juice. The best part about these site tours was talking with the industry people. I made several connections during the site tours and learnt a lot about how to get into the industry from people who have already done it. Honestly the general vibe was that it is much easier to get into the industry than people make it out to be.

Reflection

Do you think you will make it back as a returner?

I would love to go back to NCSS in 2024, but I doubt I was the stand-out student they were looking for. I was very charismatic with industry people as they were who I was kind of targeting, but I am not sure I made a significant impression on the people running NCSS.

Do you think you handled the content well?

During the latter end of the camp, I was tired and too social to give my best effort in the content, so I think I could have done better. I did get second in the programming comp (first was a group of teachers) due to my python knowledge, however I was not particularly helpful in the war games.